Spill, Huis Marseille Museum for Photography 2021

When I began

photography almost two decades ago, I was had been made to believe that my

work, my perspective and even my imagination needed to be absolute and

definite. Perhaps it is also in this absoluteness where lies the gift of the history

of photography that I was first introduced to when I started learning

photography – white, straight and male. It took a lot of unlearning and

realisation to understand that there was a much larger forest of histories that

had been kept hidden from me all along. My own larger family history is one

where my mother, a Bengali, had her family roots lie in Dhaka (Bangladesh)

pre-partition in 1947. My father, a Punjabi, on the other hand always recounted

the lives of his parents who had migrated from Lahore (current day Pakistan) to

what then went on to constitute India. Being of mixed origin would constantly

require me to locate myself quite specifically and might I say, elaboratively. Where

are you from? A question with only four words that would often require

lengthy calculations through time, geographies, caste, class, language and

sometimes even be accompanied by enthusiastic gesticulations not so different

from a complicated set of acrobatics in order to satisfy the more discerning

questioner. My works have always been interconnected and not so different from

the way a tree grows. Works that might have seemed different from one another,

at least on the surface felt like the different branches of a tree, one

reaching high out towards the sun, another spreading wider closer to the ground

in the shade of the rest of the tree. But all the different branches remained

connected to the same tree trunk.

I often work in a journal like form using a first person perspective. Besides the need to locate myself in the conversation that I seek to open up, the ‘self’ also becomes a landscape of dialogues more accessible to those who otherwise might otherwise feel provoked to resist especially considering the polarised world that we live in today. Maybe that is why in my work Snow, I’m not attempting to tell the story of Kashmir but rather unearth the seeds of denial that had been sowed into my generation who were children growing up in the India of the 1980’s-90’s and thereafter burdened with the expectation to claim Kashmir as our own without any acknowledgment of occupation and the Kashmiri call for self-determination. It was in this era of my childhood that I learnt of words such as terrorism and its association with images of Kashmir and Islam through selective sharing and obfuscating of information. This form of contemporary propaganda-making continues to be explored in other works such as the film The Lost & The Bird and the book cum installation of photographs The Coast.

The process of recognizing the self as a site of conversation began in 2005 while making an autobiographical work that was also centred around my mother who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia. I had naively assumed that I would find catharsis in the making of those pictures of my mother and my life. But the more I shared the work, people I knew as well as strangers would reach out to me with similar stories of mental illness in their own families. I realised how by making my stories their own, people found it much easier to talk about something that had long been considered a taboo here. The film Bittersweet folds into an almost fourteen minute long film a decade of my life. A narrative in my voiceover is accompanied by a music score composed out of a set of images from the film. Images are scanned on an online synthesiser and the readings of light and dark are translated into correlating frequencies of sound. Finally eight sound extractions are stitched together into a three movement music composition that become an emotional map of the memory of that time of illness and care. While Bittersweet and the installation of photographs titled Look It’s getting Sunny Outside!!! give the viewer a look into the family album that I made as an artist, in the adjacent corridor another stream of an older album is pulled out of a larger family archive. I have often wondered if an archive is more than just a repository; if it is an endless and constant accumulation. I wonder if an archive is like a flow and these two different family albums are like valves affecting that flow.

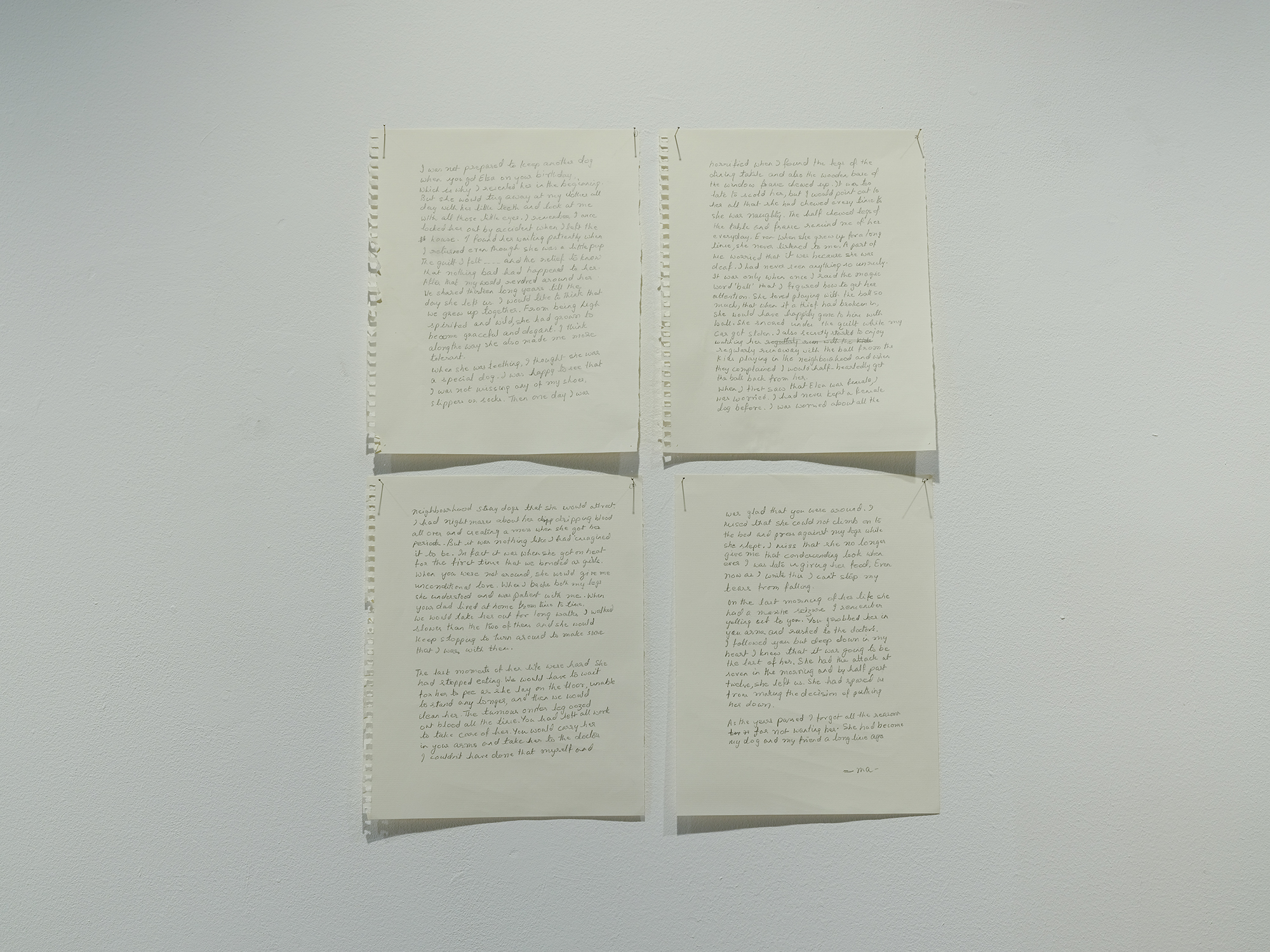

Keeping in mind, the architecture of the old, tall and narrow Dutch building that houses Huis Marseille museum, the structure of the exhibition is designed keeping in mind an accordion book. That book can be read as a double page spread open. But the sections of pages also be stretched open long into what feels like a stream of connections, quite different from the staccato rhythm of reading a usual book that is not like an accordion. At the heart of this exhibition, is the idea that image-making does not exist in isolation. The ricocheting back and forth between different projects in fact opens up the undercurrents running in each of the individual works even further. In a sense this exhibition is reflective of the nervous system. Nodes of varying densities constantly send signals to each other through a network of buses. The works in this exhibition are continuously affected by the spread of densities around them. At times, it is a physical visible connecting point between two rooms such as an extraction of my family album taped to the corridor wall. On other levels the sound from one room deliberately spills into another. Over the years the image of the image changed for me from being a ‘photograph’ to instead being either a still image or a moving image or sound or text or architecture or so on… The possibilities of what an image could be felt infinite.

I often work in a journal like form using a first person perspective. Besides the need to locate myself in the conversation that I seek to open up, the ‘self’ also becomes a landscape of dialogues more accessible to those who otherwise might otherwise feel provoked to resist especially considering the polarised world that we live in today. Maybe that is why in my work Snow, I’m not attempting to tell the story of Kashmir but rather unearth the seeds of denial that had been sowed into my generation who were children growing up in the India of the 1980’s-90’s and thereafter burdened with the expectation to claim Kashmir as our own without any acknowledgment of occupation and the Kashmiri call for self-determination. It was in this era of my childhood that I learnt of words such as terrorism and its association with images of Kashmir and Islam through selective sharing and obfuscating of information. This form of contemporary propaganda-making continues to be explored in other works such as the film The Lost & The Bird and the book cum installation of photographs The Coast.

The process of recognizing the self as a site of conversation began in 2005 while making an autobiographical work that was also centred around my mother who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia. I had naively assumed that I would find catharsis in the making of those pictures of my mother and my life. But the more I shared the work, people I knew as well as strangers would reach out to me with similar stories of mental illness in their own families. I realised how by making my stories their own, people found it much easier to talk about something that had long been considered a taboo here. The film Bittersweet folds into an almost fourteen minute long film a decade of my life. A narrative in my voiceover is accompanied by a music score composed out of a set of images from the film. Images are scanned on an online synthesiser and the readings of light and dark are translated into correlating frequencies of sound. Finally eight sound extractions are stitched together into a three movement music composition that become an emotional map of the memory of that time of illness and care. While Bittersweet and the installation of photographs titled Look It’s getting Sunny Outside!!! give the viewer a look into the family album that I made as an artist, in the adjacent corridor another stream of an older album is pulled out of a larger family archive. I have often wondered if an archive is more than just a repository; if it is an endless and constant accumulation. I wonder if an archive is like a flow and these two different family albums are like valves affecting that flow.

Keeping in mind, the architecture of the old, tall and narrow Dutch building that houses Huis Marseille museum, the structure of the exhibition is designed keeping in mind an accordion book. That book can be read as a double page spread open. But the sections of pages also be stretched open long into what feels like a stream of connections, quite different from the staccato rhythm of reading a usual book that is not like an accordion. At the heart of this exhibition, is the idea that image-making does not exist in isolation. The ricocheting back and forth between different projects in fact opens up the undercurrents running in each of the individual works even further. In a sense this exhibition is reflective of the nervous system. Nodes of varying densities constantly send signals to each other through a network of buses. The works in this exhibition are continuously affected by the spread of densities around them. At times, it is a physical visible connecting point between two rooms such as an extraction of my family album taped to the corridor wall. On other levels the sound from one room deliberately spills into another. Over the years the image of the image changed for me from being a ‘photograph’ to instead being either a still image or a moving image or sound or text or architecture or so on… The possibilities of what an image could be felt infinite.

While I began my

journey earnestly as a documentary photographer working on specific ‘subjects’,

in recent years I started to get drawn more to the workings of the larger image

system. Scepticism of photography came about not to criticise a kind of image

making that believes in the idea of ‘truth’ – in fact I believe it is a

direction we will need to return to trusting more in passing time – but rather

because of the recognition of the image system that has always allowed the

usurping of power through the manipulation of the ideas of ‘truth’. These

image-traps are not new, they have existed from the time the first drawings

were made. Only now, the densities of these webs are almost impossible to

completely decipher and this is what the governments here in India and

elsewhere where they are relatively free of accountability, continue to exploit

to remain in power. This is also why in the exhibition, I use a glass of water as a camera

to make images (an inverted one), posters with glitches and sound frequencies

that make water flow backwards on the screen of the installed I-pad since the

interface of a screen is what determines today, what is real and what is not.

In the red room, as one walk closer to the historically iconic images of Nehru,

the first prime minister and Ambedkar who wrote the Indian constitution, images

of Modi, the current majoritarian prime minister and his henchman Amit Shah

start to emerge out of those iconic images. The words to the preamble to the

constitution become more unstable the longer that you look at them. It’s our

constitution that the current government is threatening to change. In an

atmosphere of widespread revisionism by the majoritarian government in India

and increasing punitive action against criticism of the government. The red

room at Huis Marseilles brings together an excerpts of such image experiments

that might lie close to the foundations of the larger, more coherent bodies of

work being exhibited. This preparation for the future of image making in codes

and abstracts are in contrast of older works like Pati, a film made in

2010 at a time when there was still a little more elbow space here as an

individual to be more critical, politically. These more experimental works are

part of a long time endeavour to continuously update vocabularies of subterfuge

that are required to bypass state controlled algorithms. We are living in a

time when histories are being recorded more so in images than in words and

governments in power recognize that. Amongst these works there is also one

where a needle seems to levitate in the air fighting hard to reach at the tear

in my trousers that are lying on the floor. It is an ode to my mother who has

been part of so much of what I do. Having been raised primarily by her, I

grew up watching her perform rituals of care such as folding my clothes away

and often mending and stitching the rips and tears in my clothes. Much of my

vocabulary for my process has been derived from what I would see my mother do:

stitching, weaving, knitting, folding. I recognize that deeply ingrained these

acts of are in my process when I think of the layering and accumulating going

on in my work. It has always been about building, mending and putting works

together.

Spill is NOT a retrospective exhibition even if it shows works that span across times. It is about the continuous unfixing of images. It is not thematic but methodological where storytelling lies at the heart of it. It is an exhibition where spillages across the different works help reveal my milieu. It is about the notations, citations and the footnotes, that are often remain invisible in the background even if for many of us as artists the ‘art’ is nothing but a residue of something far bigger. The exhibition is about the clashes and contradictions between different works that open up fault lines where there may be new sprouting. I keep think about the bucket in the installation in the Light Court in Huis Marseille museum that has the speaker, the hose and water. As the frequency of sound and its vibrations change, drops of water start to splash out. That splashing makes me more aware of whether the bucket is nearly empty or almost full. It makes me think of the flow of the water running out of the hose. Is it a gushing or just a trickle? It makes me think of the time needed to fill up that bucket. It makes me think of the valve along with the flow of water. Until I turn on the flow of water, that bucket is just a bucket. But maybe this exhibition at its core is about that bucket with drops of water splashing out of it.

September 2021

Spill is NOT a retrospective exhibition even if it shows works that span across times. It is about the continuous unfixing of images. It is not thematic but methodological where storytelling lies at the heart of it. It is an exhibition where spillages across the different works help reveal my milieu. It is about the notations, citations and the footnotes, that are often remain invisible in the background even if for many of us as artists the ‘art’ is nothing but a residue of something far bigger. The exhibition is about the clashes and contradictions between different works that open up fault lines where there may be new sprouting. I keep think about the bucket in the installation in the Light Court in Huis Marseille museum that has the speaker, the hose and water. As the frequency of sound and its vibrations change, drops of water start to splash out. That splashing makes me more aware of whether the bucket is nearly empty or almost full. It makes me think of the flow of the water running out of the hose. Is it a gushing or just a trickle? It makes me think of the time needed to fill up that bucket. It makes me think of the valve along with the flow of water. Until I turn on the flow of water, that bucket is just a bucket. But maybe this exhibition at its core is about that bucket with drops of water splashing out of it.

September 2021