Growing like a tree

I can see my mother’s hands as she carefully folds the sleeves of my freshly ironed shirt into a compact bundle which she then stacks upon a pile of washed clothes still smelling of detergent lying by her side on her already messy bed. She pauses over the fresh hole she has just found that sits proudly in an otherwise respectable piece of attire. She runs her fingers lightly over the edges of the tear, presses her lips and shakes her head in disapproval and then goes on to continue making her folds. It is obvious that she has already hatched a plot to rectify what she considers an aberration in her son’s image. She only needs to catch the right moment, when I’m the least bit suspecting and with not much will to protest that makeover. This constant game of folding and unfolding of newly washed clothes remains the last of the umbilical cord tying my mother and me. My mother knows very well that I am completely dependent on her for love and care. I know very well that I’m completely dependent on her for the lack of my own washing machine. It has taken me almost three decades to realise how my mother had weaved together the foundations from which I could make sense of the world around me. The folding of clothes, the clickety-clack of knitting needles and the weighted pauses before aiming the wet end of thread into a needle’s eye… It was the ordinariness of such daily domestic chores that projected into what I might have then called my artistic process. It has taken me another ten years to discover that the system of care and nurture I understand myself to be growing within, both as a person and as an artist, in fact extends further across my friends, companions, conversations, events and gestures experienced along the way; all of which continue to mould and remould me into the person I am today.

Growing Like A Tree lays out an incomplete blueprint of my experience of community and friendship where photography forms the nucleus of this large and pulsating nervous system that entangles our lives together. Artists Jaisingh Nageswaran, Sean Lee and Munem Wasif take on the notions of home and belonging in their respective works. I Feel Like A Fish by Jaisingh marks a coming to terms with a history – and a present – that he had been trying to escape until the recent lockdown forced him to move back to his family village. With this work Jaisingh hopes to pay tribute to his grandmother – Ponnuthai – who in 1953 transformed her home into a school for Dalit children as a resistance against the upper caste community in her village in Vadipatti, outside Madurai. Sean Lee’s body of photographs Two People and Munem Wasif’s film Kheyal intertwine residues of memory and a constant search for home with the half-spaces between the real and the imaginary. While Sean uses the element of touch and the camera’s playfulness to look for a moment of emotional healing between his parents, Wasif’s inquiry into the solitude of an otherwise teeming city of Old Dhaka remains unresolved, much like the memories of his childhood. The present remains as ephemeral as the past. Music flows out of an empty window, milk is drawn out of a well of water each time the bucket is lowered into its depths and a horse whiter than milk unexpectedly appears in a dark alley. We are never quite sure whose memory or imagination this is: The protagonist’s? The artist’s? Or ours? These fragile states of existence that flow between the confines of an apartment in Singapore, a village outside Madurai and the old decrepit lanes in Old Dhaka continue to spill into the larger show.

Ephemerality is a tool used by Aishwarya Arumbakkam, whose installation of photographs titled ka Dingiei takes on the thread ofa child Arlangki’s quest to find ka Dingiei, an ancient mythical creature rumoured to have the power to restore balance in nature, against the backdrop of Lama Punji, a small Khasi village struggling due to the environmental damage inflicted on them from mining. This departure from a more familiar forms of storytelling of social issues doesn’t attempt to take on the burden of bearing witness but rather cuts through the numbness of an image-soaked world by shifting the perspective to the way one might imagine a grandparent narrating a story to a grandchild. Almost 15 years ago, when I started making photographs of my mother who was ill at the time,this question of honesty had stopped me from making more photographs. It wasn’t the kind of honesty that photography has forever been burdened with: that unrealistic expectation of being representative of some sort of truth that, for some inexplicable reason, we continue to burden photography with. Instead, the ‘honesty’ that mattered to me at the time was an alignment of my work with the intent with which I made it. That early work, Life is Elsewhere, was intended to be a journal but towards the end of it, I began to recognise how photographs could perform and invoke in the viewer a desired reaction. If this was the case, then was I starting to perform for the camera as well? Was I unconsciously or even consciously trying to use a certain kind of photography to protect myself from points of vulnerability? In that case, was my work even ‘real’? You see, for someone who had to teach himself everything from scratch and more importantly, who barely found his feet in this world in general, there could be nothing worse than an onset of doubt whose depths seemed to swallow them in its flow. Around that time in 2008, I had started to work with children of Anjali House in Siem Reap, Cambodia and I was charmed by the way they moved with the camera: carefree, raw, and unaware of the baggage that came with being a photographer. Intuitive and awkward, they were unabashed in the physicality of their movements in relation to the camera, as well as their approach to whatever and whoever they photographed. This made me realise the stiffness in the formality, or more precisely, the consciousness of my own process. It became clear that I had to unlearn everything I knew. In fact, I had to let go of being a photographer altogether and instead try and be a son who might be photographing his mother. The photographs by the children of Anjali House form one of the many hearts of this exhibition. They are a constant reminder of the magic in the way one might look at the world, no matter how cynical one might feel as an artist at times. This magic also runs through the works by the artists Katrin Koenning, Sathish Kumar and Sarker Protick, each offering multiple avenues.

Sathish Kumar has often described his work Town Boy as a collection of unremarkable moments. It is in its lightness that this series of photographs emanates more of his upbringing in the small town of Kanchipuram than the metropolis of Chennai that he now calls home. Collisions is an amalgamation of short films that Katrin Koenning began making a few years ago on her phone of stormy nights under the tube of a streetlight, the first rays of the morning sun and reflections in water. Katrin’s world is defined by light that is strongly anchored in the physical world and in the present moment. Sarker Protick, her friend and erstwhile collaborator stretches light (as well as sound) in an almost metaphysical realm. Origins had originally been conceived to exist inside its own box. A hypnotic soundscape along with a video of red light dripping into the night skies was meant to alter perception within that box. However, for this exhibition Protick transforms his enclosed box into a portal-like freestanding screen, as if folding a sock inside out.

In 2020 Arundhati Roy wrote about the ongoing pandemic being a portal into another world. I keep thinking about the other side. What will that world be like? Will it be more empathetic? Or is all that we have been experiencing really that world already? Ever since I became a photographer there was this constant expectation that I rooted myself in an identity. I might have located that identity in authorship or pegged it to specific socio-political geographies. This constant need to identify as an ‘Indian artist’ feels even more absurd at a time when the state is trying to fix onto its people the criteria of who does or does not constitute an Indian citizen. It has always been awkward for me to situate works within geographic identities. Given the times we are now living in, I’m even more hesitant to do so because I no longer know what ‘being Indian’ means. How do I separate artists from Bengal who might have more of a shared history with artists from Bangladesh and yet consider them in unison with others from Tamil Nadu? How do I acknowledge the Kashmiri want for political autonomy and yet conveniently ascribe important works made by Kashmiri artists an Indian for the sake of art? How do I contest the issue of who is or isn’t an Indian citizen that is is being forced on us, while ignorantly identifying works from a prism of having been made by ‘Indian artists’ – a grouping that is determined and occupied by upper-caste, mostly English and Hindi speaking people, mostly straight men, who are either from North India or from metropolitan cities or from privileged backgrounds, most of whom are using similar standards for ‘good’ or ‘bad’ photography from a homogeneous perspective.

Growing Like A Tree lays out an incomplete blueprint of my experience of community and friendship where photography forms the nucleus of this large and pulsating nervous system that entangles our lives together. Artists Jaisingh Nageswaran, Sean Lee and Munem Wasif take on the notions of home and belonging in their respective works. I Feel Like A Fish by Jaisingh marks a coming to terms with a history – and a present – that he had been trying to escape until the recent lockdown forced him to move back to his family village. With this work Jaisingh hopes to pay tribute to his grandmother – Ponnuthai – who in 1953 transformed her home into a school for Dalit children as a resistance against the upper caste community in her village in Vadipatti, outside Madurai. Sean Lee’s body of photographs Two People and Munem Wasif’s film Kheyal intertwine residues of memory and a constant search for home with the half-spaces between the real and the imaginary. While Sean uses the element of touch and the camera’s playfulness to look for a moment of emotional healing between his parents, Wasif’s inquiry into the solitude of an otherwise teeming city of Old Dhaka remains unresolved, much like the memories of his childhood. The present remains as ephemeral as the past. Music flows out of an empty window, milk is drawn out of a well of water each time the bucket is lowered into its depths and a horse whiter than milk unexpectedly appears in a dark alley. We are never quite sure whose memory or imagination this is: The protagonist’s? The artist’s? Or ours? These fragile states of existence that flow between the confines of an apartment in Singapore, a village outside Madurai and the old decrepit lanes in Old Dhaka continue to spill into the larger show.

Ephemerality is a tool used by Aishwarya Arumbakkam, whose installation of photographs titled ka Dingiei takes on the thread ofa child Arlangki’s quest to find ka Dingiei, an ancient mythical creature rumoured to have the power to restore balance in nature, against the backdrop of Lama Punji, a small Khasi village struggling due to the environmental damage inflicted on them from mining. This departure from a more familiar forms of storytelling of social issues doesn’t attempt to take on the burden of bearing witness but rather cuts through the numbness of an image-soaked world by shifting the perspective to the way one might imagine a grandparent narrating a story to a grandchild. Almost 15 years ago, when I started making photographs of my mother who was ill at the time,this question of honesty had stopped me from making more photographs. It wasn’t the kind of honesty that photography has forever been burdened with: that unrealistic expectation of being representative of some sort of truth that, for some inexplicable reason, we continue to burden photography with. Instead, the ‘honesty’ that mattered to me at the time was an alignment of my work with the intent with which I made it. That early work, Life is Elsewhere, was intended to be a journal but towards the end of it, I began to recognise how photographs could perform and invoke in the viewer a desired reaction. If this was the case, then was I starting to perform for the camera as well? Was I unconsciously or even consciously trying to use a certain kind of photography to protect myself from points of vulnerability? In that case, was my work even ‘real’? You see, for someone who had to teach himself everything from scratch and more importantly, who barely found his feet in this world in general, there could be nothing worse than an onset of doubt whose depths seemed to swallow them in its flow. Around that time in 2008, I had started to work with children of Anjali House in Siem Reap, Cambodia and I was charmed by the way they moved with the camera: carefree, raw, and unaware of the baggage that came with being a photographer. Intuitive and awkward, they were unabashed in the physicality of their movements in relation to the camera, as well as their approach to whatever and whoever they photographed. This made me realise the stiffness in the formality, or more precisely, the consciousness of my own process. It became clear that I had to unlearn everything I knew. In fact, I had to let go of being a photographer altogether and instead try and be a son who might be photographing his mother. The photographs by the children of Anjali House form one of the many hearts of this exhibition. They are a constant reminder of the magic in the way one might look at the world, no matter how cynical one might feel as an artist at times. This magic also runs through the works by the artists Katrin Koenning, Sathish Kumar and Sarker Protick, each offering multiple avenues.

Sathish Kumar has often described his work Town Boy as a collection of unremarkable moments. It is in its lightness that this series of photographs emanates more of his upbringing in the small town of Kanchipuram than the metropolis of Chennai that he now calls home. Collisions is an amalgamation of short films that Katrin Koenning began making a few years ago on her phone of stormy nights under the tube of a streetlight, the first rays of the morning sun and reflections in water. Katrin’s world is defined by light that is strongly anchored in the physical world and in the present moment. Sarker Protick, her friend and erstwhile collaborator stretches light (as well as sound) in an almost metaphysical realm. Origins had originally been conceived to exist inside its own box. A hypnotic soundscape along with a video of red light dripping into the night skies was meant to alter perception within that box. However, for this exhibition Protick transforms his enclosed box into a portal-like freestanding screen, as if folding a sock inside out.

In 2020 Arundhati Roy wrote about the ongoing pandemic being a portal into another world. I keep thinking about the other side. What will that world be like? Will it be more empathetic? Or is all that we have been experiencing really that world already? Ever since I became a photographer there was this constant expectation that I rooted myself in an identity. I might have located that identity in authorship or pegged it to specific socio-political geographies. This constant need to identify as an ‘Indian artist’ feels even more absurd at a time when the state is trying to fix onto its people the criteria of who does or does not constitute an Indian citizen. It has always been awkward for me to situate works within geographic identities. Given the times we are now living in, I’m even more hesitant to do so because I no longer know what ‘being Indian’ means. How do I separate artists from Bengal who might have more of a shared history with artists from Bangladesh and yet consider them in unison with others from Tamil Nadu? How do I acknowledge the Kashmiri want for political autonomy and yet conveniently ascribe important works made by Kashmiri artists an Indian for the sake of art? How do I contest the issue of who is or isn’t an Indian citizen that is is being forced on us, while ignorantly identifying works from a prism of having been made by ‘Indian artists’ – a grouping that is determined and occupied by upper-caste, mostly English and Hindi speaking people, mostly straight men, who are either from North India or from metropolitan cities or from privileged backgrounds, most of whom are using similar standards for ‘good’ or ‘bad’ photography from a homogeneous perspective.

What I have been observing over the years are collective flows in terms of movement and exchange between photographers across political, geographical and cultural boundaries. If I were to specify a nucleus within this larger ecosystem, it would be Kathmandu, Nepal, because of access to free movement from around the larger region. An osmosis-like relationship with photographers across a range of boundaries has started to seep through, with each searching for new ways to grow as an artist and each having at stake something in common that is far more urgent than photography. Bunu Dhungana, Yu Yu Myint Than, Nida Mehboob, Reetu Sattar and Nepal Picture Library trigger responses to the breakdown of the world around them. Bunu took to photography later than most others but this only made her hungrier to make meaningful work. Confrontations is her push-back against the stigma of being an unmarried woman, where she uses her body as a weapon against societal expectations imposed on her. The body is also central to Yu Yu Myint Than’s Sorry, Not Sorry. Broken emulsions through chemical manipulation nudge us into a psychological landscape in the aftermath of a relationship. The feeling of her world falling apart is mirrored in the ongoing breakdown of Myanmar’s political economy. Yu Yu’s is the only book in the exhibition that is meant to be read.

Shadow Lives by Nida Mehboob brings insight into the persecution of the Ahmadis in Pakistan. Her photographs built on metaphors and childhood stories don’t situate themselves in events in a way that many of us on the outside might expect, but rather, bring to the fore the mundanity of oppression. In ‘How to be an ally with Kashmir: War stories from the kitchen’by Omer Aijazi as well as the documentary cookbook ‘The Gaza Kitchen’, the author talks about the need to listen and unlearn. The kitchen becomes a place for trust and an invitation there turns into a welcoming of conversations. With equal ordinariness, Nida weaves in memories of childhood trauma collected over the years. In ‘Padosan’, the 1968 cult classic Bollywood film, a music teacher (Mehmood) and a bumbling suitor (Sunil Dutt) vie for the affections of the character played by Saira Banu. This battle reaches its crescendo in the lyrics of ‘Ek Chatur Naar’, where neighbouring houses dish out songs to each other for one-upmanship. This wafting in and out of music through windows had long-represented a companionship between neighbours. In Harano Sur (Lost Tune) by Reetu Sattar, this companionship and love is starkly overcome by a cacophony of 65 harmoniums playing out of tune, alluding to society’s descent into chaos. As Reetu pulls away from memory into the present, Nepal Picture Library drifts back into time. From the larger entanglements of histories, Nepal Picture Library unravels a thread from the resistance against the outlawing of Nepal’s democratically elected parliament by the royal family between 1960 and 1990. The thread belongs to two women, Sushila Shrestha and Shanta Manavi, who reminisce about their underground passages into Nepal’s Communist Party.

I initially sought out Farah Mulla’s audio work Aural Mirror because it felt like a necessary disruption within the show that primarily looks at a different way of ‘seeing’. But it then occurred to me how Farah has often used therapy as an impetus for aural experiences. I also noticed that she always anticipates that the viewer might have unfettered relationships with her work, similar to the ways in which children can experience sound (and image). This motivation recalled the very reasons I started making photographs many years ago. I only happened to make photographs. I’m no longer sure if Aural Mirror is really a disruption -even if itrelies on taking in the visitor’s presence and transmuting it into noise within its never-ending feedback loops. The mirror that Farah seeks to hold up is meant to be her own, but the salve is also for me to make it mine. Also in the exhibition is my personal copy of Sent a letter by Dayanita Singh. Remembering my history as a young beneficiary of her anonymous gifts (hundreds of rolls of film), when I was always struggling to find the means to continue making work and realising the overlaps that she presently shares with many other lives within this exhibition, the unopened book becomes a marker for such invisible but precious parts of one’s journey. These often go unacknowledged even if the echoes of the seemingly quiet gestures live far beyond the moment that they were intended for, like dropping a small pebble into a still pond and then watching ripples slowly reach the edges. In recurrences.

I peer through the doorway into my mother’s bedroom and see that she is almost done fixing my shirt. The criss-cross of stitches holds down the patch nicely. Despite initial protests against the idea of the covering up of the hole that I assumed projected my persona, I already feel accustomed to living with it. The more I think about the intricate stitches the more I sense a new unease slowly inflecting this essay, which now starts to feel like a failure. In an attempt to contextualise the works of all the artists, I fear I’ve unwittingly fixed them, and the larger exhibition, into another box. As I watch my mother’s hands gracefully knotting the thread loop to form a new stitch and follow that cross over to another, I wonder if what I’ve written so far has only been that first stitch with many more still to go. I think of Wasif’s and Reetu’s shared memories of music flowing through neighbouring windows and wonder how those memories might have been entangled in their shared lives even if their retracing feels so divergent. I find my own memories imaginary and intertwined with what I experience. My mother’s parents had left their homes behind in Dhaka to move to this place that I am told is India. Both Reetu and Farah seek out solace in noise as a breaking point but that noise sits equally in Bunu’s self-portraits as it does in works by Nida and Yu Yu and the Nepal Picture Library. It has taken me a long time to realise that an archive is not the bucket but the endlessly flowing tap. I’ve always thought of the archive to be a containment. But maybe it’s more like valve that enables flows passing through. Like Dubai. Like everyone else who is part of this show.

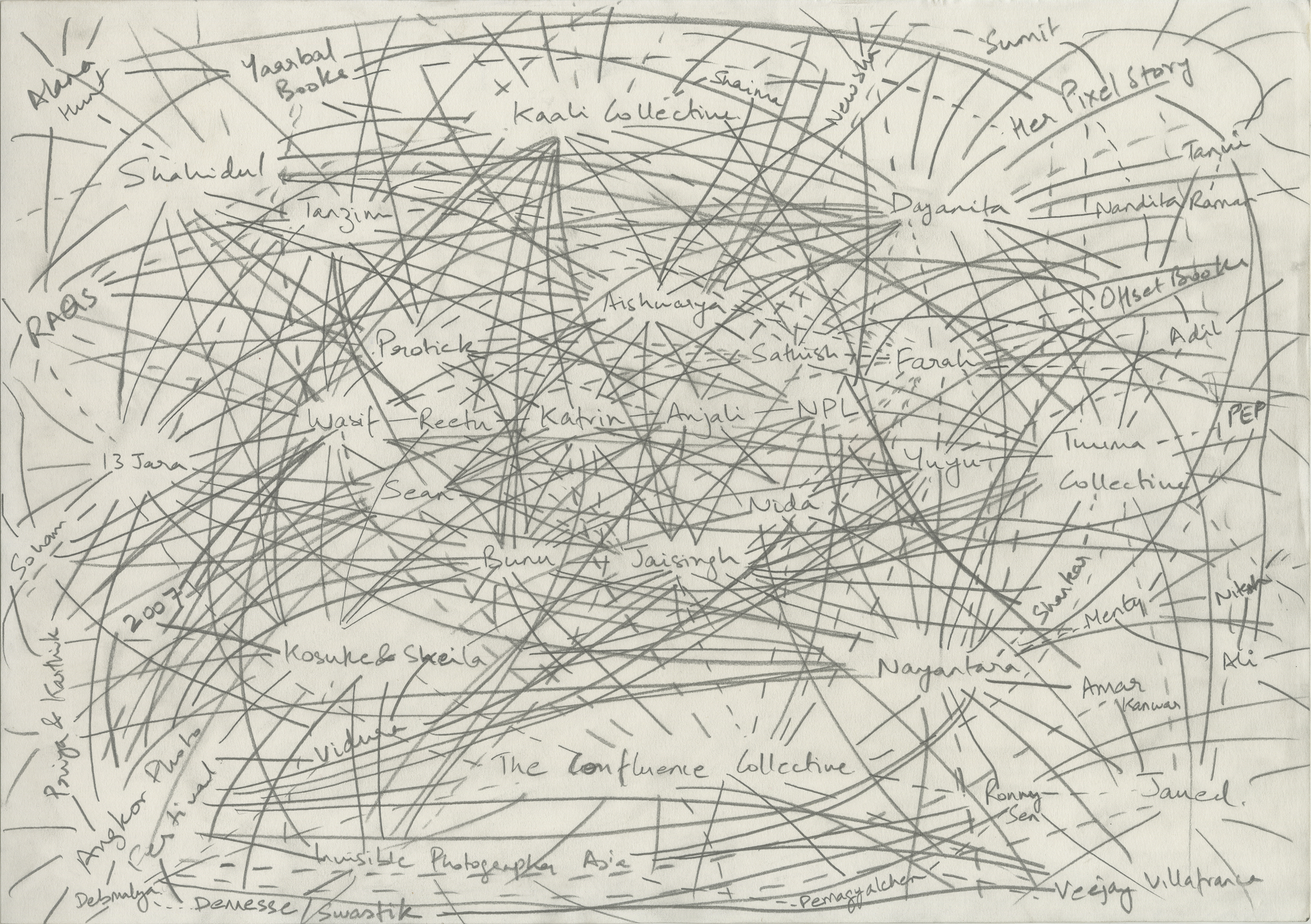

In 2007 Sean, Wasif and I were batch-mates at a workshop in Siem Reap, Cambodia. Sean and I had been roommates there. I was photographing my mother and Sean was photographing his family. I remember us talking about the need to touch other lives as much as the need to be touched by others through works made and experienced. The arguments with Wasif around photography, life and us losing our hair over apple shakes made by an old lady in front of our little guesthouse had turned into a daily affair. I think of Protick and his relationship with Katrin as a collaborator, with Wasif as a student and with Aishwarya as a mentor. Both Sean and Katrin have mentored the children at Anjali House and I feel tempted to believe that some of the magic has rubbed off on them as well. Onthe bus journeys with Jaisingh and Sathish along the Tamil coastline they would become my eyes and ears with which I would experience the landscape and make work. Little does anyone know that without the two of them, and so many others, much of my own work would not exist. The more I watch new stitches being sown into my shirt, the more this interconnectedness gets clearer. In the beginning I had imagined each work and artist to be a node within this system, but those nodes have now quietly slipped into the spaces in-between. And what I had initially feared to be a box now starts to morph itself into a Rubik’s Cube. Every new twist and turn brings in a new combination and the box never remains constant. I now imagine the branches of the tree connected to a single trunk – even if the roots have grown far deeper than I’ll ever know. I try and imagine what kind of a tree my tree would be. I remember that when I had started photography I had been shown a beautiful tree. Its tall trunk shot up towards the sky from the lone hilltop that it grew out from. I remember wanting to sit on the tree but I was never able to climb up. I now remember how years ago Priyadarshini (Ravichandran) and Karthik (Subramanian) took me to Theosophical Society in Chennai to see the Banyan trees. I marvelled at one giant tree after another as they led me further into a dense forest of giant Banyans. Their branches touched and overlapped creating a canopy so thick that it formed a patch of shade in the city on a hot summer day. Only the barren centre of that forest remained lit with sunlight. It turned out that the forest had once been a single tree. The massive tree trunk – which even had a bus stop named after it – had died and its aerial roots became trees. I’m now able to see my tree more clearly. It is an incomplete aerial root tree surrounded by a forest of other aerial root trees – younger, stronger and far more generous and expansive than mine. Each finds its own way to the light. The thing is that it was never about the tree itself but the growing of the tree.

Dubai, January 20, 2021

Shadow Lives by Nida Mehboob brings insight into the persecution of the Ahmadis in Pakistan. Her photographs built on metaphors and childhood stories don’t situate themselves in events in a way that many of us on the outside might expect, but rather, bring to the fore the mundanity of oppression. In ‘How to be an ally with Kashmir: War stories from the kitchen’by Omer Aijazi as well as the documentary cookbook ‘The Gaza Kitchen’, the author talks about the need to listen and unlearn. The kitchen becomes a place for trust and an invitation there turns into a welcoming of conversations. With equal ordinariness, Nida weaves in memories of childhood trauma collected over the years. In ‘Padosan’, the 1968 cult classic Bollywood film, a music teacher (Mehmood) and a bumbling suitor (Sunil Dutt) vie for the affections of the character played by Saira Banu. This battle reaches its crescendo in the lyrics of ‘Ek Chatur Naar’, where neighbouring houses dish out songs to each other for one-upmanship. This wafting in and out of music through windows had long-represented a companionship between neighbours. In Harano Sur (Lost Tune) by Reetu Sattar, this companionship and love is starkly overcome by a cacophony of 65 harmoniums playing out of tune, alluding to society’s descent into chaos. As Reetu pulls away from memory into the present, Nepal Picture Library drifts back into time. From the larger entanglements of histories, Nepal Picture Library unravels a thread from the resistance against the outlawing of Nepal’s democratically elected parliament by the royal family between 1960 and 1990. The thread belongs to two women, Sushila Shrestha and Shanta Manavi, who reminisce about their underground passages into Nepal’s Communist Party.

I initially sought out Farah Mulla’s audio work Aural Mirror because it felt like a necessary disruption within the show that primarily looks at a different way of ‘seeing’. But it then occurred to me how Farah has often used therapy as an impetus for aural experiences. I also noticed that she always anticipates that the viewer might have unfettered relationships with her work, similar to the ways in which children can experience sound (and image). This motivation recalled the very reasons I started making photographs many years ago. I only happened to make photographs. I’m no longer sure if Aural Mirror is really a disruption -even if itrelies on taking in the visitor’s presence and transmuting it into noise within its never-ending feedback loops. The mirror that Farah seeks to hold up is meant to be her own, but the salve is also for me to make it mine. Also in the exhibition is my personal copy of Sent a letter by Dayanita Singh. Remembering my history as a young beneficiary of her anonymous gifts (hundreds of rolls of film), when I was always struggling to find the means to continue making work and realising the overlaps that she presently shares with many other lives within this exhibition, the unopened book becomes a marker for such invisible but precious parts of one’s journey. These often go unacknowledged even if the echoes of the seemingly quiet gestures live far beyond the moment that they were intended for, like dropping a small pebble into a still pond and then watching ripples slowly reach the edges. In recurrences.

I peer through the doorway into my mother’s bedroom and see that she is almost done fixing my shirt. The criss-cross of stitches holds down the patch nicely. Despite initial protests against the idea of the covering up of the hole that I assumed projected my persona, I already feel accustomed to living with it. The more I think about the intricate stitches the more I sense a new unease slowly inflecting this essay, which now starts to feel like a failure. In an attempt to contextualise the works of all the artists, I fear I’ve unwittingly fixed them, and the larger exhibition, into another box. As I watch my mother’s hands gracefully knotting the thread loop to form a new stitch and follow that cross over to another, I wonder if what I’ve written so far has only been that first stitch with many more still to go. I think of Wasif’s and Reetu’s shared memories of music flowing through neighbouring windows and wonder how those memories might have been entangled in their shared lives even if their retracing feels so divergent. I find my own memories imaginary and intertwined with what I experience. My mother’s parents had left their homes behind in Dhaka to move to this place that I am told is India. Both Reetu and Farah seek out solace in noise as a breaking point but that noise sits equally in Bunu’s self-portraits as it does in works by Nida and Yu Yu and the Nepal Picture Library. It has taken me a long time to realise that an archive is not the bucket but the endlessly flowing tap. I’ve always thought of the archive to be a containment. But maybe it’s more like valve that enables flows passing through. Like Dubai. Like everyone else who is part of this show.

In 2007 Sean, Wasif and I were batch-mates at a workshop in Siem Reap, Cambodia. Sean and I had been roommates there. I was photographing my mother and Sean was photographing his family. I remember us talking about the need to touch other lives as much as the need to be touched by others through works made and experienced. The arguments with Wasif around photography, life and us losing our hair over apple shakes made by an old lady in front of our little guesthouse had turned into a daily affair. I think of Protick and his relationship with Katrin as a collaborator, with Wasif as a student and with Aishwarya as a mentor. Both Sean and Katrin have mentored the children at Anjali House and I feel tempted to believe that some of the magic has rubbed off on them as well. Onthe bus journeys with Jaisingh and Sathish along the Tamil coastline they would become my eyes and ears with which I would experience the landscape and make work. Little does anyone know that without the two of them, and so many others, much of my own work would not exist. The more I watch new stitches being sown into my shirt, the more this interconnectedness gets clearer. In the beginning I had imagined each work and artist to be a node within this system, but those nodes have now quietly slipped into the spaces in-between. And what I had initially feared to be a box now starts to morph itself into a Rubik’s Cube. Every new twist and turn brings in a new combination and the box never remains constant. I now imagine the branches of the tree connected to a single trunk – even if the roots have grown far deeper than I’ll ever know. I try and imagine what kind of a tree my tree would be. I remember that when I had started photography I had been shown a beautiful tree. Its tall trunk shot up towards the sky from the lone hilltop that it grew out from. I remember wanting to sit on the tree but I was never able to climb up. I now remember how years ago Priyadarshini (Ravichandran) and Karthik (Subramanian) took me to Theosophical Society in Chennai to see the Banyan trees. I marvelled at one giant tree after another as they led me further into a dense forest of giant Banyans. Their branches touched and overlapped creating a canopy so thick that it formed a patch of shade in the city on a hot summer day. Only the barren centre of that forest remained lit with sunlight. It turned out that the forest had once been a single tree. The massive tree trunk – which even had a bus stop named after it – had died and its aerial roots became trees. I’m now able to see my tree more clearly. It is an incomplete aerial root tree surrounded by a forest of other aerial root trees – younger, stronger and far more generous and expansive than mine. Each finds its own way to the light. The thing is that it was never about the tree itself but the growing of the tree.

Dubai, January 20, 2021