Rooftop

1

I open my eyes to the familiar whirring of the creaky old fan at my feet. Sunlight has managed to break through the defenses and it crawls across the room, letting long fuzzy shadows creep along the walls. I should have got thicker curtains when I had the chance but now it’s a bit late for that. It’s past noon already and I know that my daily breakfast ritual of muesli and yoghurt awaits me. It is practical and I’m glad that I don’t have to bother my brain immediately with the thought of what to feed myself next. I set about getting my bearings on the day as I try and wobble out of bed but the grogginess clings on to me, almost as if to keep me company while the world tries to shield itself from an enemy so tiny and invisible that we repeatedly look past it in search of someone else to fix as the culprit.

As I write this, it has been over two months since I met anyone else and this has hit nobody harder than my mother. Moving out of my parents’ house some years ago seems to have brought its own share of trauma. Every visit back there would end up in reminders that their house (and home) was in fact also mine. Taking my dirty laundry back with me was the last flicker of hope my mother had that I still needed her. Buying a new washing machine would mean my moving out and into a new apartment larger than a room, to accommodate the new companion. So this had always been pooh-poohed. That I was in fact too stingy to buy my own washing machine was occasionally considered. With the lockdown, this umbilical cord with my mother has been broken, I think.

I’m without many clothes to wear now and I’m done with washing what few I have, by hand every other day, because I’m stuck with clothes mostly meant for March in Europe that I wasn’t able to replace before the lockdown began. So I find myself naked most of the time except for some special occasions, like in the evenings when I dress up to step out to the terrace to water the plants that are constantly gasping for life, reminding me of my failures as a caretaker. When I do catch a glimpse of myself in the mirror, I see a dishevelled face with a body below that seems to be falling apart quite gloriously, like a swollen grape left out for too long. I imagine this lockdown as a perfect excuse, even if I had already started to leave open the top button of my trousers sometime last year.

2

I returned to India in the second week of March to the news that members of the party in power – the BJP – had thrown a cow urine drinking party to ward off the virus. Another minister, not to be outdone, suggested that cow dung be placed in front of houses for better protection. There was news of recently born twins named Covid and Corona. Another baby soon made the news for being named Sanitizer Singh. Somewhere in between, the minister who had earlier thrown the urine party, was arrested after an enthusiastic volunteer fell ill. The space of resistance was abdicated by the artist long ago and of late it has been the stand up comedian who has started to take the fight to the government. And now young electronic musicians have decided to make a mish-mash festival of the ‘Go Corona Go’ slogans being regularly chanted by ministers when they run out of answers to questions about procuring safety equipment for health workers.

This time of absurdity quickly morphed into horror when news of migrant workers walking back home started to trickle out. People leaving on foot to return to their villages, making journeys that were at times up over a thousand kilometres. They preferred to die back home than in the cities that had abandoned them. Day after day, stories and images of women, children, men, young, old, disabled, on the move, all of them suffering, flooded the every day lives of those of us who have only the pandemic to worry about. Social Distancing is the hot phrase today. But there is a tiny but sustained movement run by people who I trust to change the term to ‘Physical Distancing But Social Solidarity’ because it seems that it is Doctors, Health Workers, Muslims, Migrants, Watchmen, Workers, Vegetable Sellers, Barbers, Foreigners and even those who might faintly look Chinese that we need to be Socially Distanced from. Or so… people clanging their empty utensils to the tune the government would like us to believe. Even today as I start to write, I see that the story of Yakub, the Muslim and Amrit, the Hindu is needed to resuscitate some conscience back into us, temporarily. As the two friends made their long journey back home, Amrit fell sick and was immediately discarded by the travelling group of migrants. His friend Yakub was the only one who stayed with him. Amrit died soon after.

All this… while the government shamelessly celebrates itself and continues to focus on its plans of constructing an atrociously expensive new parliament house that it hopes will reflect a legacy removed from those who founded the constitution, while people succumb to hunger. Instead of helping ease the largest mass migration in recent history, all it does is ask people to be ‘self sufficient’. By now this trickle of stories has run itself into a flood. It doesn’t help to learn of the increasing strangulation of Kashmir and its people and also of political arrests here in India. Students, Activists and anybody else who dares to raise a voice against the government. Well, mostly Muslims, if I am to be honest. The pendulum of my existence at times swings in all directions but these days guilt and helplessness seem to

be its two loves. Arundhati Roy had written about this pandemic being a portal into another world. I keep thinking about that other world on the other side. What will that world be like? Will it be more empathetic? Or is all this really that world already?

I open my eyes to the familiar whirring of the creaky old fan at my feet. Sunlight has managed to break through the defenses and it crawls across the room, letting long fuzzy shadows creep along the walls. I should have got thicker curtains when I had the chance but now it’s a bit late for that. It’s past noon already and I know that my daily breakfast ritual of muesli and yoghurt awaits me. It is practical and I’m glad that I don’t have to bother my brain immediately with the thought of what to feed myself next. I set about getting my bearings on the day as I try and wobble out of bed but the grogginess clings on to me, almost as if to keep me company while the world tries to shield itself from an enemy so tiny and invisible that we repeatedly look past it in search of someone else to fix as the culprit.

As I write this, it has been over two months since I met anyone else and this has hit nobody harder than my mother. Moving out of my parents’ house some years ago seems to have brought its own share of trauma. Every visit back there would end up in reminders that their house (and home) was in fact also mine. Taking my dirty laundry back with me was the last flicker of hope my mother had that I still needed her. Buying a new washing machine would mean my moving out and into a new apartment larger than a room, to accommodate the new companion. So this had always been pooh-poohed. That I was in fact too stingy to buy my own washing machine was occasionally considered. With the lockdown, this umbilical cord with my mother has been broken, I think.

I’m without many clothes to wear now and I’m done with washing what few I have, by hand every other day, because I’m stuck with clothes mostly meant for March in Europe that I wasn’t able to replace before the lockdown began. So I find myself naked most of the time except for some special occasions, like in the evenings when I dress up to step out to the terrace to water the plants that are constantly gasping for life, reminding me of my failures as a caretaker. When I do catch a glimpse of myself in the mirror, I see a dishevelled face with a body below that seems to be falling apart quite gloriously, like a swollen grape left out for too long. I imagine this lockdown as a perfect excuse, even if I had already started to leave open the top button of my trousers sometime last year.

2

I returned to India in the second week of March to the news that members of the party in power – the BJP – had thrown a cow urine drinking party to ward off the virus. Another minister, not to be outdone, suggested that cow dung be placed in front of houses for better protection. There was news of recently born twins named Covid and Corona. Another baby soon made the news for being named Sanitizer Singh. Somewhere in between, the minister who had earlier thrown the urine party, was arrested after an enthusiastic volunteer fell ill. The space of resistance was abdicated by the artist long ago and of late it has been the stand up comedian who has started to take the fight to the government. And now young electronic musicians have decided to make a mish-mash festival of the ‘Go Corona Go’ slogans being regularly chanted by ministers when they run out of answers to questions about procuring safety equipment for health workers.

This time of absurdity quickly morphed into horror when news of migrant workers walking back home started to trickle out. People leaving on foot to return to their villages, making journeys that were at times up over a thousand kilometres. They preferred to die back home than in the cities that had abandoned them. Day after day, stories and images of women, children, men, young, old, disabled, on the move, all of them suffering, flooded the every day lives of those of us who have only the pandemic to worry about. Social Distancing is the hot phrase today. But there is a tiny but sustained movement run by people who I trust to change the term to ‘Physical Distancing But Social Solidarity’ because it seems that it is Doctors, Health Workers, Muslims, Migrants, Watchmen, Workers, Vegetable Sellers, Barbers, Foreigners and even those who might faintly look Chinese that we need to be Socially Distanced from. Or so… people clanging their empty utensils to the tune the government would like us to believe. Even today as I start to write, I see that the story of Yakub, the Muslim and Amrit, the Hindu is needed to resuscitate some conscience back into us, temporarily. As the two friends made their long journey back home, Amrit fell sick and was immediately discarded by the travelling group of migrants. His friend Yakub was the only one who stayed with him. Amrit died soon after.

All this… while the government shamelessly celebrates itself and continues to focus on its plans of constructing an atrociously expensive new parliament house that it hopes will reflect a legacy removed from those who founded the constitution, while people succumb to hunger. Instead of helping ease the largest mass migration in recent history, all it does is ask people to be ‘self sufficient’. By now this trickle of stories has run itself into a flood. It doesn’t help to learn of the increasing strangulation of Kashmir and its people and also of political arrests here in India. Students, Activists and anybody else who dares to raise a voice against the government. Well, mostly Muslims, if I am to be honest. The pendulum of my existence at times swings in all directions but these days guilt and helplessness seem to

be its two loves. Arundhati Roy had written about this pandemic being a portal into another world. I keep thinking about that other world on the other side. What will that world be like? Will it be more empathetic? Or is all this really that world already?

3

I live in a Barsati, a one-room apartment on the terrace, atop an old residential building in the south of the city. Delhi was always known for its rooftop life. In some seasons especially around August you’d see people flying kites from their rooftops. When the day would get really hot you would sleep on the roof and breathe in the cool summer night. And during the first rains when you woke up with the soaked smell of earth, you’d climb upstairs to be in the rain – that was a time when it was still beautiful to get wet in the rain. In the sunny Delhi winter people would soak themselves in light. It was still common to spot a grandmother give her grandchild an oil head massage or an adolescent body poring over a book in one corner; carom or cards being played in another. On a charpoy, a plate would be full of empty pea pods or finely chopped Bhindi (Okra) lying in wait, the smell of spices wafting its way upstairs. But as material lives improved, we stopped coming up out on to the rooftop terrace.

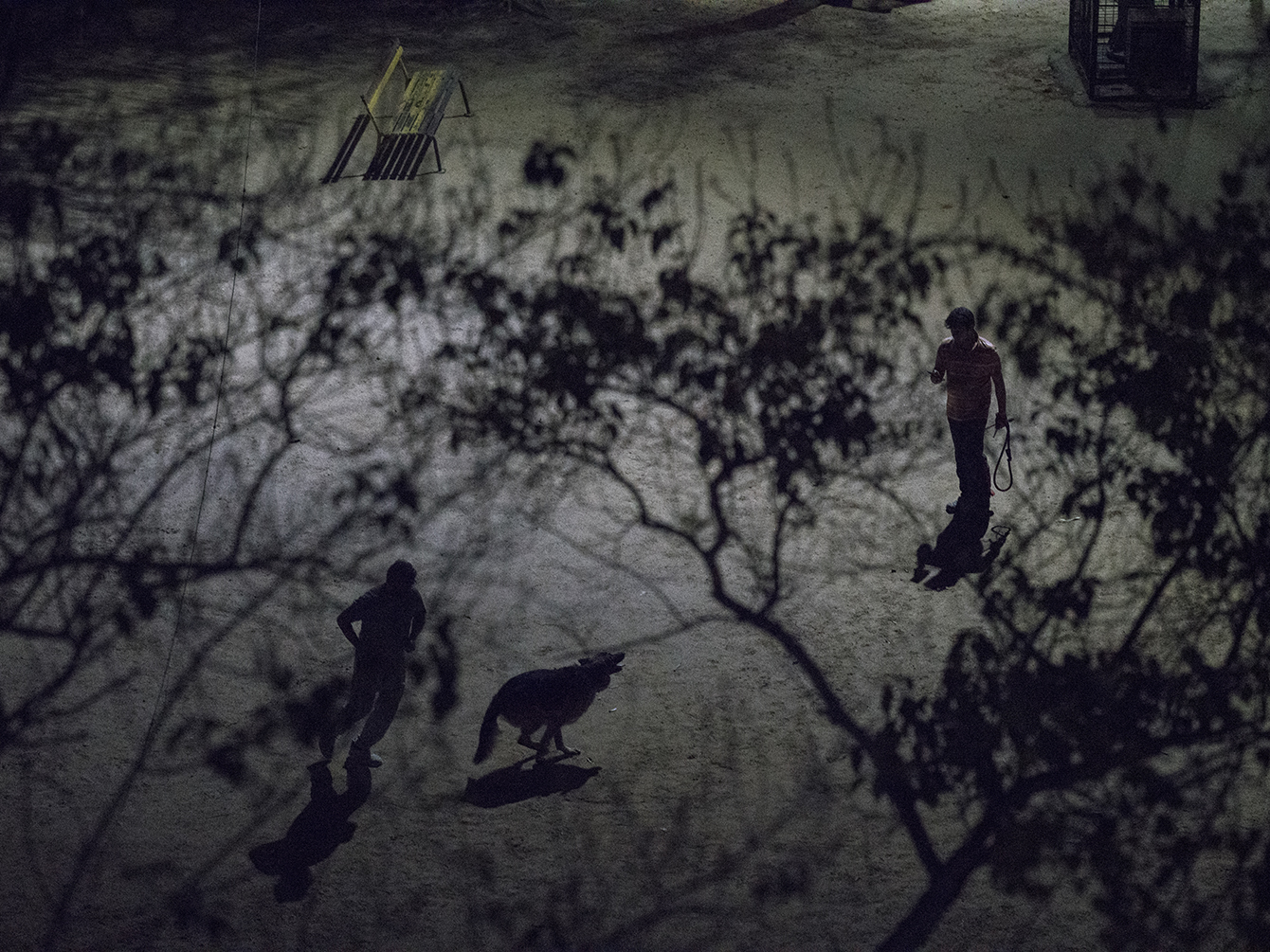

Now that I’m alone and stuck in my apartment, every evening after it cools down, I go out and climb on top of my room to see as far as I can in every direction. From my rooftop, I notice that the sky is a lot bigger than I remember. I also see more birds, some familiar, some that I don’t recognise. This daily ritual makes me forget that I’m alone. On the neighbouring rooftops I see others do the same. In between the ugly plastic water tanks a couple sometimes steals a kiss. The kind old gentleman on the opposite side never fails to raise his arm and give a smile. There is a beautiful German Shephard dog who is my neighbour who loves to look at something, down over the terrace wall. In the beginning the family a few rooftops away always came on to their rooftop with much gusto. One day they’d fly a kite. On another they’d slip a tennis ball into an old stocking. That stocking would be tied to a water pipe with a rope. They would now be able to play wall tennis without having to worry about the ball falling off the rooftop.

At that time of great enthusiasm the lockdown had just begun and the end was not too far away. Two weeks, is what we had been told. But as we went through phase after phase, life above continued to evolve. The second extension brought with it a sudden emptiness but now into the fourth phase, the rooftops are starting to fill up again. The family now sits in melancholic silence, each one lost in a different thought, but there is a peculiar calm of acceptance. The only one in this elevated neighbourhood with any sense of constant morale is the neighbour who works out on the terrace. Over the last two months the 6 o’clock grunts have seamlessly merged into birdsongs filling up the space. He knows that I carry with me a camera and waves at me enthusiastically, lifting his children in his arms signalling me to make a photograph. WhatsApp numbers are shouted out across the trees and photographs and messages exchanged. I’m not sure if I’d have even noticed him under normal circumstances. If I had, I’d surely have avoided him because it would be easy to profile him into being of a different political leaning. Politics is all that matters these days. You are either a ‘bhakt’ or a ‘liberandu’. Yet he is the only one who would wave at me right from the beginning without any suspicion. He raises a thumbs up and gets back to his children. In between his workout sets he makes sure to do a quick dance with his kids and even lift them up in the air.

I realise that I’ve never felt more like a voyeur as I have at this moment. The hunger to touch makes my eyes forage through the concrete and the trees and even the skyline. I turn around and catch a pair of familiar eyes watching me. The friendly old man in the building on the opposite side seems to have been checking on his air conditioning unit. I notice the gold shadows slowly start to merge into blackness and I know that the saddest time of the day is over. I raise my arm to wave goodbye and he flashes a smile back as I make my way down the ladder. Damn, now I need to work out what to eat for dinner!’

May 2020

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

I live in a Barsati, a one-room apartment on the terrace, atop an old residential building in the south of the city. Delhi was always known for its rooftop life. In some seasons especially around August you’d see people flying kites from their rooftops. When the day would get really hot you would sleep on the roof and breathe in the cool summer night. And during the first rains when you woke up with the soaked smell of earth, you’d climb upstairs to be in the rain – that was a time when it was still beautiful to get wet in the rain. In the sunny Delhi winter people would soak themselves in light. It was still common to spot a grandmother give her grandchild an oil head massage or an adolescent body poring over a book in one corner; carom or cards being played in another. On a charpoy, a plate would be full of empty pea pods or finely chopped Bhindi (Okra) lying in wait, the smell of spices wafting its way upstairs. But as material lives improved, we stopped coming up out on to the rooftop terrace.

Now that I’m alone and stuck in my apartment, every evening after it cools down, I go out and climb on top of my room to see as far as I can in every direction. From my rooftop, I notice that the sky is a lot bigger than I remember. I also see more birds, some familiar, some that I don’t recognise. This daily ritual makes me forget that I’m alone. On the neighbouring rooftops I see others do the same. In between the ugly plastic water tanks a couple sometimes steals a kiss. The kind old gentleman on the opposite side never fails to raise his arm and give a smile. There is a beautiful German Shephard dog who is my neighbour who loves to look at something, down over the terrace wall. In the beginning the family a few rooftops away always came on to their rooftop with much gusto. One day they’d fly a kite. On another they’d slip a tennis ball into an old stocking. That stocking would be tied to a water pipe with a rope. They would now be able to play wall tennis without having to worry about the ball falling off the rooftop.

At that time of great enthusiasm the lockdown had just begun and the end was not too far away. Two weeks, is what we had been told. But as we went through phase after phase, life above continued to evolve. The second extension brought with it a sudden emptiness but now into the fourth phase, the rooftops are starting to fill up again. The family now sits in melancholic silence, each one lost in a different thought, but there is a peculiar calm of acceptance. The only one in this elevated neighbourhood with any sense of constant morale is the neighbour who works out on the terrace. Over the last two months the 6 o’clock grunts have seamlessly merged into birdsongs filling up the space. He knows that I carry with me a camera and waves at me enthusiastically, lifting his children in his arms signalling me to make a photograph. WhatsApp numbers are shouted out across the trees and photographs and messages exchanged. I’m not sure if I’d have even noticed him under normal circumstances. If I had, I’d surely have avoided him because it would be easy to profile him into being of a different political leaning. Politics is all that matters these days. You are either a ‘bhakt’ or a ‘liberandu’. Yet he is the only one who would wave at me right from the beginning without any suspicion. He raises a thumbs up and gets back to his children. In between his workout sets he makes sure to do a quick dance with his kids and even lift them up in the air.

I realise that I’ve never felt more like a voyeur as I have at this moment. The hunger to touch makes my eyes forage through the concrete and the trees and even the skyline. I turn around and catch a pair of familiar eyes watching me. The friendly old man in the building on the opposite side seems to have been checking on his air conditioning unit. I notice the gold shadows slowly start to merge into blackness and I know that the saddest time of the day is over. I raise my arm to wave goodbye and he flashes a smile back as I make my way down the ladder. Damn, now I need to work out what to eat for dinner!’

May 2020